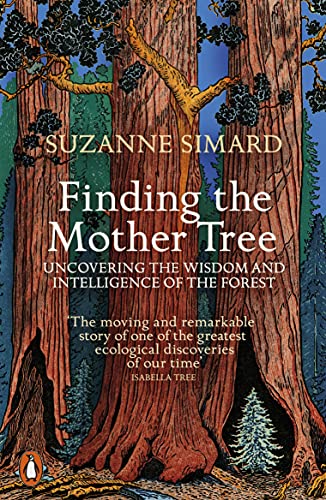

Suzanne Simard: Finding the Mother Tree

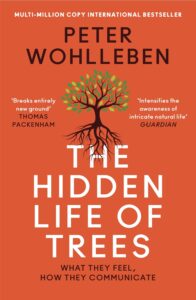

Peter Wohlleben: The Hidden Life of Trees

Byline: These two books, by pioneers on either side of the Atlantic, will forever change the way you look at woods and forests. They explain our growing understanding of the deep, complex and fascinating connectivity between trees.

Suzanne Simard and Peter Wohlleben work in the forests of Canada and Germany respectively. Each tells their story of discovery in their own style, revealing how trees communicate through an immense web of fungi, nurturing, protecting and sustaining each other.

Simard’s book weaves her personal life story with her transformative research work, from her early days in the forest service in British Columbia to becoming Professor of Forest Ecology at the University of British Columbia and a world-renowned expert in her field.

At the outset, her work was often dismissed by a male-dominated culture that was set in its ways. Those ways were decimating the landscape, removing all supposed competition to commercial wood production and creating monocultures, lacking resilience and biodiversity.

Step by step, Simard’s research began to show the folly of this approach, as the magic of the mycorrhizal networks was revealed. Initially, the exchanges were shown between trees of the same species but then a much wider trading tapestry began to be revealed, culminating in the discovery of the Mother Trees of the book’s title, that recognise and support their own kin.

Her story is one of great bravery, in the face of industry intransigence and abuse, working in brown bear terrain, balancing work and motherhood, and then battling cancer – potentially linked to her early work with radioactive substances.

It makes for a moving and remarkable tale that pulls you along, rooting for the author and the forests. Ultimately, her work constitutes a huge breakthrough in our understanding of the natural world and has resulted in a shift to much more sustainable practices, but also a shift in our fundamental perspective. “The scientific evidence is impossible to ignore,” she writes. “The forest is wired for wisdom, sentience and healing. This is not a book about how we can save the trees. This is a book about how the trees might save us.”

Wohlleben’s book – in which Simard’s work is often referenced – is less personal in nature but equally well written and gripping. He sets out to explain the social network of the forests, drawing on his own observations working for Germany’s forestry commission and from the ever-growing body of scientific work from around the world.

The result is a series of themed chapters that provide a wonderful picture of the interconnectedness, with amazing facts piled upon amazing facts. Such as the way trees have adapted to fight off attackers, whether beetles or giraffes (in the case of the latter, not only repelling the animals themselves but communicating to neighbouring trees to take action).

The author poses intriguing questions such as, how do trees “remember”? If, for instance, it takes a certain number of days of warm weather before trees to start to produce the chemicals for spring growth, how do they measure and store knowledge of that time period? Do trees feel pain or have awareness of their surroundings?

Wohlleben clearly has a deep love of woods and forests, explaining the incredible processes of life, death and regeneration he has observed in his woodland.

The two books complement each other, as will others, such as Merlin Sheldrake’s Entanglement, which takes a ground-up view, honing in on the fungal networks on which almost all life relies. The lessons on interconnectedness are ones that we would do well to learn – or relearn (indigenous people understood them well) – if we are to have any chance of turning around the current climate and ecological crises.